No title, No body, No thing

Patrick Lundberg

11 March – 11 June, 2023

In No title, No body, No thing, Patrick Lundberg presents a selection of minimal abstract wall works, adapted to the gallery space at Whangārei Art Museum. In this exhibition, Lundberg asks the viewer to consider their own habits when engaging with art, as his works demand close inspection to be fully appreciated. Despite the small size of their individual components, they also require that the viewer visually traverses the entire terrain of the gallery to take in their scope.

Ki roto i a No title, No body, No thing, ka tohaina e Patrick Lundberg he kohinga he mahinga pakitara tūrehurehu itiiti, i urutautia ki te tauwhanga huarewa ki Te Whare Taonga Toi o Whangārei. Ki roto i tēnei whakaatūranga ka uiuia e Lundberg te kaimātakitaki kia whai whakaaro ki a rātou ake tikanga i a rātou e tūtakitaki ana ki te toi, inā ka whakakuene kia āta whakamatawai kia riro katoa mai te whakamaiohatanga. Ahakoa te nohinohi o te nui o ia waehanga, he herenga tōna kia hōpara te kaimātakitaki i te katoa papa o te huarewa kia riro mai ko te tirohanga.

These works can be broken down into three categories: first, a group of works that consist of a network or skein of small, rounded, or faceted painted components made of a variety of materials; second, a series of vertical format works on narrow strips of material that function somewhat more like traditional paintings; and third, a series of small, cylindrical wall works, also painted.

Ka taea te wetewete ēnei mahi kia heke iho ki ngā momo e toru: tuatahi, he kohinga mahi ka kapi katoa mai he tūhononga, he pōkai iti, he waehanga waituhi whakakoki, kōpio rānei, ka hangatia mai i te momo rawa; tuarua, he rārangi hōputu poutū ki runga rawa kōwharawhara kūiti ka rāwekeweke tūā-rite ki ngā waituhi tuku iho; ā, tuatoru, he rārangi iti, o ētahi mahi rango mō te pakitara, anō hoki kua waituhia.

The pin-like wall works cover large areas of the gallery, circumscribing expansive zones while also opening out into the surrounding architecture. These works tempt the viewer to consider each element as a micro-painting, due to their bright colours and decorative, often expressive patterns and designs, but they also draw their attention to the voids and distances between each element. The implied connections between each point take on a new significance when viewed as a whole, like constellations in the night sky.

Ngā mahi ā-pātū, āhua pinepine ka whāriki takiwā rarahi ki te huarewa, taiāwhio nei i ngā kauhanga raurarahi i te wā anō e whakapuaki ana ki roto i te hoahoanga takai. Ko ēnei mahi ka whakawai. Ko ēnei mahi ka whakawai i te kaimātakitaki kia whaiwhakaaro ko ia pūmotu hei waituhi moroiti, inā ko ngā tae kanapu me te whakarākei, ia wā, rawa ko ngā whakairo whakapuaki me ngā whakaahua, engari ka whakawai anō hoki rātou ki ngā korekore me ngā tawhititanga wawaenga ia pūmotu. Ko ngā tūhonohononga ki waenganui ia tohu ka hiki ake i tētahi hiranga hou inā tirohia ki tōna katoatoa, pērā ki ngā kāhui ki te rangi ā pō.

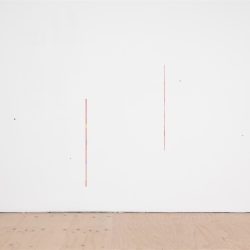

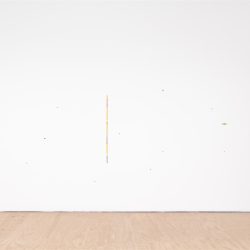

Meanwhile, the vertical works, by pushing the physical dimensions of the painting to its logical extreme, playfully question expectations and conventions around the format. Again, their dimensions require that they be viewed close-up, or else dissolve into an indistinct slash on the wall. Due to their essentially linear format, their oscillating patterns ask to be read in an equally linear fashion, as though the eye were a cursor scrubbing through a video of scintillating, amorphous colour fields.

Nā wai rā, ko ngā mahi poutū, mā te whakatāuke i ngā ahunga ōkiko o te waituhi ki tōna tōpito whakakaupapa, pātaitia tākarokaro i ngā kawatau me ngā tikanga e pā ana ki te hōputu. Anō, ko o rātou rahinga ka whai herenga kia tirohia pātatatia, kia memeha koia rānei ki roto i tētahi hahae ākahukahu ki runga i te pakitara. Nā tō rātou tino hōputu rārangi, kō o rātou whakairo kōpiupiu ka uiui kia pānuitia mā roto i tētahi auaha rārangi taurite, pērā tonu ko te whatu he peha e hūkui ana puta noa i tētahi ataata whakamāhanahana, mātai muramura, āhuahanga kore,

Lastly, the smaller cylindrical works could be read as individual, cast-off nodes, discrete from the larger archipelagos but likewise continuing their poetics of scale and distance. Isolated as they are, they exhibit an even greater sense of fragility, jewel-like oases in a desert of wall-white.

Ka mutu, ko ngā mahi rango nohinohi ake ka taea te pānui hei takitahinga, he tīpona whiua kia makere, nahenahe mai i ngā whakamāurutanga nunui ake engari waihoki moroki tonu tā rātou toikupu o te āwhata me te tawhititanga. He noho mōtu ko tā rātou, ka whakaatu he tino tairongo makuhane, kōmanawa mehe kahurangi ki roto i te koraha pakitara mā.

As the title of the exhibition suggests, all three series explore the idea of absence and emptiness, as a result of the way the works push the blinding white expanse of the traditional gallery wall to the forefront of the viewer’s attention. As in many areas of life, a space that appears barren or empty can teem with detail, nuance, and interconnectedness on a closer, more measured inspection.

E ai ki te whakahau o te taitara whakaatūranga, ko ngā raupapa e toru katoa ka totoro i te whakaaro o te korenga me te hemanga, he whakaotinga o te ara ka whakatāuke ngā mahi i te whakarahi mā paiheretanga o te rahinga mā o te pakitara tuku iho ki te tōmuatanga o te aro a te kaimātakitaki. Kia rite ki ngā takiwātanga koiora, he wā ka whakaahua tūpā, kautahanga rānei ka engaenga me te taipitopito, Motuhake me te whanaungatanga tūhonohono mā ki runga i te tino tirohanga whakaine.

—

Moving a point traces a line, move the line and you’ve produced a plane, move the plane and you’ve shaped something solid. The basic factors of three-dimensional space can be constructed through this simple geometric progression, in which the point is the primitive, generative element whereby pictorial space unfolds its form. Points and lines are like the syntax through which a meaningful visual language is made; meaningless in themselves, they constitute meaning’s conditions of possibility.

Drawing and painting activate the generative potential of the point as it moves along a linear trajectory. Understood as the result of movement, the real principle of pictorial space is time—the time it takes for a subject to construct it. Perhaps all pictures then, whatever their complexity, can be conceptually reduced to the mobile point at their origin—the graphic mark of the brush, pencil, or pixel that condenses a virtual universe awaiting elaboration. In its abstraction, the point is an element that can be manipulated by the artist at will, either mimetically reconstituting the appearance of the world, or transforming its appearance across the endlessly modifiable surface of the space formed through its variable extension. It’s this formal plasticity that grounds historical claims for modernist painting’s indexation of subjective autonomy.

Patrick Lundberg’s work self-consciously deploys these elementary geometric elements in both the shape of his painting’s supports, and in the basic motifs he marks on their surface. Figure and ground continually redouble each other in a circular recapitulation—the geometric constituents of pictorial space alternating equivocally between the shape of the support, their distribution across the wall, and the finely wrought painterly singularities revealed in the repetition of each gestural inscription on their surface. Points and lines, eddies and regresses…

Like all work that situates itself within the historical lineage of modernist painting and its later minimalist developments, Lundberg’s work risks the problem of emptiness—the possibility of sterile repetitions, exhausted seriality, vacuous variations on an obscure metaphysical theme without end, subjective expression tending towards a self-cancelling negation and the world itself being bracketed in favour of an exploration of the means by which it is represented. Sometimes, it feels like we are left with the false concreteness of perception only, the requirement of conceptual labour rendered unreal or futile.

But I find this work interesting for precisely these reasons and risks, and its discreet formal charm and metaphysical subtext offers a constant provocation. In the end, its beauty is disarming, and it’s for that reason that I’m made perversely uncomfortable. To tell the truth, there is an aestheticism in this work that I simply vibe with, and I’m not sure what to make of that.

Perhaps this discomfort arises because, as with all formalisms, what I discern in this work is in fact a historical subtext—a repression of aspects of social reality in which I locate the work’s paradoxical expressivity. Perhaps I’m sympathetic to this foreclosure or recognise in it an expression of a historically specific truth about artistic sublimation, to which I am also bound.

Silence, emptiness and abstraction are strange, secret values that painting conserves at its core and which are always threatened by an internal corruption that would render them cheap, facile or banal. In his own way, Lundberg’s rigorous yet playful consistency makes these values shine, avoiding their negative inversion. He treats them in his work with a pleasurable lightness and intelligence, without pathos. He is not unaware or unaffected by the issues that so much contemporary art strives to deal with, but he resolutely moves along his own chosen path. I think it’s for this reason that his artistic practice inspires such respect among his peers—even, and perhaps especially, when their practices markedly differ.

Time is Lundberg’s primary concern and the key theme that organises his work and his thinking around it. The specific works within his oeuvre that most forcefully bring this to our attention are what he informally calls ‘sets’: collections of ‘points’ fashioned out of globes of resin, wood, marbles, and sometimes clay or brass. In certain iterations the points are in fact cylindrical forms, or are faceted. In any case, they constitute the discrete moments of multi-part works with variable dimensions that can be compositionally adapted to each wall that they happen to be installed on.

In conversation, Patrick has indicated that the logic of the sets will orient his approach to the installation of No title, No body, No thing. In this regard, sets are an apt descriptor, and their expansion to the governing logic of the exhibition as a whole makes sense when we consider that a set is simply a distinct, bounded collection of different elements. What is an exhibition, if not a set of artworks, a collection of parts configured within an ensemble of relations to one another that produces a nominal unity?

In each of Patrick’s sets the artwork is distinguished by the number of its distinct elements, but the relationships that obtain between them are contingent—their dimensions are variable, and form an open structure that incorporates an essential indeterminacy into the work’s formal unity, as there is no fixed state that the artist has definitively decided to present to the viewer.

Transience and variation are constants in this art—ironically durable qualities that the work repetitively exemplifies on each occasion it is presented. They are works that cannot be taken in in an instant, but only ever as they are revealed, part-by part, across a temporal horizon through which the viewer moves from moment to moment. Their peculiar temporality is attested to by their difficulty in being photographed. Taken as a whole, each part diminishes to the threshold of invisibility when the camera attempts to capture it all within its frame, and yet a detailed shot of a section, though it could be considered a work in and of itself, is only ever a single, partial fragment, always pointing beyond itself to the next node in the network, the next sequence in a perceptual slide down the line. This experience attests to the formal rigor of Lundberg’s project. The proof of his ambition to render temporal experience visible is asserted in the work’s tendential disappearance within the documentation that attempts to preserve a record of its form.

In a photograph, the architecture of the space seems to predominate. In the presence of the work, this architectural container, large as it is, is integrated as a subordinate aspect of the art—another element in the set. Thus, a temporal truth, mundane or profound, is integrated within its structure, and verified as such in our experience of the time it takes to see it. We only have to step into its forcefield.

Shiraz Sadikeen