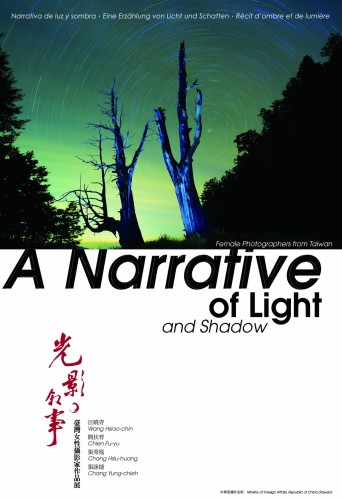

A Narrative of Light and Shadow

Narrative of Light and Shadow – Female Photographers from Taiwan features five photographic series by Wang Hsiao-chin, Chien Fu-yu, Chang Hsiu-huang and Chang Yung-chieh.

Wang Hsiao-chin uses portraiture to explore the 15 years after her own pregnancy. She uses her experience of motherhood and a meditation on the passage of time in pursuit of self-understanding and “remembrance of things past.”

Chien Fu-yu’s involvement with the women’s movement began in the 1980s. She began working as a photographer for such magazines during the Martial Law period (1949-1987), using her camera to record the women’s movement, at which time she also began to shoot female portraits. Chien says: “Using the camera and pen as tools to care about and record people and things — especially women — is what got me into photography in the first place, and continues to be a commitment of mine to this day.”

Chang Hsiu-huang took up photography by chance, initially taking pictures of flowers and gradually developing an interest in landscape photography. It was through her photographic work that she came to realise that Taiwan, although small, has a wealth of beautiful scenery, a rich folk culture and extensive cultural relics. “Taiwan’s small size means it is easy to switch between enjoying mountain scenery to appreciating an ocean view,” she says.

Chang Yung-chieh was born on Taiwan’s outlying island of Penghu. In 1996 Chang returned to her hometown to establish the Hexi Cultural Workshop, dedicated to recording the archipelago’s cultural and oral history. The ceremonies centered on the Eternal Treasure Ship have a strong seafaring flavour and are a very important part of the folk beliefs of Taiwan’s coastal communities. The Eternal Treasure Ship series, shot between 2003 and 2010, gives a record of the most important ceremonies involved, such as greeting the king, patrolling, and sending off the king, and their associated activities.

The Heirs of the Clouded Leopard series records the way of life of the Rukai aboriginal people of Kochapongane Village, in southern Taiwan’s Pingtung County. In 1977, faced with a changing society, the villagers uprooted en masse and relocated to a new place by Beidawu Mountain, above the lower reaches of Nan-ailiao.

Exhibition supported by the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Auckland.

Wang Hsiao-ching

Wang, a Ph.D. graduate from the School of Arts and Communication at the UK’s University of Brighton, has long

focused on such themes as female identity and visual culture, producing paintings, videos, mixed media works and

installations on these subjects. A full-time artist and artistic director of Ching Tien Art Space, Wang is also an assistant

professor at National Dong Hwa University’s Department of Arts and Design and Taipei Municipal University of

Education’s Department of Visual Arts. Since her “Marriage” series was exhibited in 1997 at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Wang has produced a steady output of work for solo and group exhibitions in Taiwan, the UK and other countries. In 2002 she was named one of Taiwan’s distinguished female photographers in the book History of Contemporary Taiwan Women Artists.

“Mother’s time chart” is a self-portrait series redolent with historical meaning, in which Wang doubles as the female

photographer and one of the protagonists. Beginning when she is visibly pregnant, the series continues at intervals for

the next 15 years with pictures taken using a self-timer. Many of the pictures have their backdrop the immediate

preceding shot to record the progression in the personal relationships between her, her husband and her child; the

piling up of the images and the background illustrate how the parent-child relationship accumulates over time. Wang

uses her experience of motherhood and a meditation on the passage of time in pursuit of self-understanding and

“remembrance of things past.” She uses the artistic portrayal of the mother-son relationship to tease out the actors’ inner thoughts, to prove that motherhood is not just a form of self-sacrifice, but something to be savoured and which can contribute to rich and colourful personal growth.

Chen Fu-yu

Chien’s involvement with the women’s movement began in the 1980s. She began working as a photographer for such

magazines during the Martial Law period (1949-1987), using her camera to record the women’s movement, at which

time she also began to shoot female portraits. Chien says: “Using the camera and pen as tools to care about and

record people and things — especially women — is what got me into photography in the first place, and continues to

be a commitment of mine to this day.”

Most women’s history remains submerged in the general tide of historical narrative. By using images to record women’s stories, Chien writes history from a female point of view. The criterion for choosing the material for this series is that the subjects must have had substantial success in their fields, have contributed to society and shown concern for the people. Priority is given to older women, as there is much to be gained from their accumulated life experiences. The pictures selected cover the stories of five Taiwanese women from different fields: Taiwan’s first professional female painter, Chen Jin; first female reporter following the end of Japanese colonial rule (1895-1945), Yao Min-xuan; poetess Chen Xiuxi; the extraordinary Atayal woman Taibasi Nuogan; and pathologist Li Feng. These five women’s historical records reflect various and fascinating life experiences. This series is not simply a work of art, but also a historical record of Taiwan’s development.

Chang Hsiu-huang

Chang started off as an ordinary office worker at a company involved with exports to Japan, rather than as a

professional photographer. Yet the pressures of a busy job did nothing to diminish her love of photography, through

which she found a spiritual outlet.

Chang took up photography by chance, initially taking pictures of flowers and gradually developing an interest in

landscape photography. It was through her photographic work that she came to realise that Taiwan, although small,

has a wealth of beautiful scenery, a rich folk culture and extensive cultural relics. “Taiwan’s small size means it is

easy to switch between enjoying mountain scenery to appreciating an ocean view,” she says.

In “Light and shadow,” Chang uses her mature photographic skills to record the cycle of Taiwan’s seasons and reveal

the charm of nature’s changes. She uses her lens to show Taiwan’s varied and fascinating landscape, ranging from

the beauty of the Pacific to the majesty of the Central Mountains, capturing the island’s natural grace.

Chang Yung-chieh

Chang Yung-chieh, born on Taiwan’s outlying island of Penghu, is a professional photographer who has won three Golden Tripod awards for her work for Chinese-language Humanity and Living Psychology magazines. She has had

solo exhibitions at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Eslite Gallery and numerous cultural centres, and has also displayed her work in Amsterdam, New York and Paris.

In 1996 Chang returned to her hometown on Penghu to establish the Hexi Cultural Workshop, dedicated to recording

the archipelago’s cultural and oral history. Her writing has a unique poetic quality and her lens shows her deep feelings for Penghu. Her camera captures the moment; she has an affinity for what her subjects are thinking. Through her lens, Chang quietly expresses her boundless love for her hometown. The beauty of the people, things and scenery

of Chang’s hometown guides her vision like a lighthouse: Her ultimate objective is to capture the everyday life of the

people. Through her photography, one sees the life and religious beliefs of Penghu’s people — aspects that strongly

motivated Chang at the start of her career and remain her lifelong theme.